Set sail for Japan, fascinating land of the rising sun!

Organized by the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, this exhibitionexplores the fruitful encounter between East and West from the late nineteenth century to the end of the Belle Époque through a presentation of ukiyo-e prints, or “images of the floating world,” and pieces of Japanese decorative art, in dialogue with paintings, prints and refined objects produced by renowned artists in Europe and the United States.

The approximately 130 works in the exhibition, by a hundred different Japanese, American and European artists including Vincent Van Gogh, Claude Monet, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri Matisse, Edgard Degas, Édouard Vuillard, Edvard Munch, Paul Gauguin, Mary Stevenson Cassatt, Louis C. Tiffany, William H. Bradley and others, come from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which has one of the largest and most renowned collections of Japanese, American and European art of the period.

The Birth of a Major Artistic Current

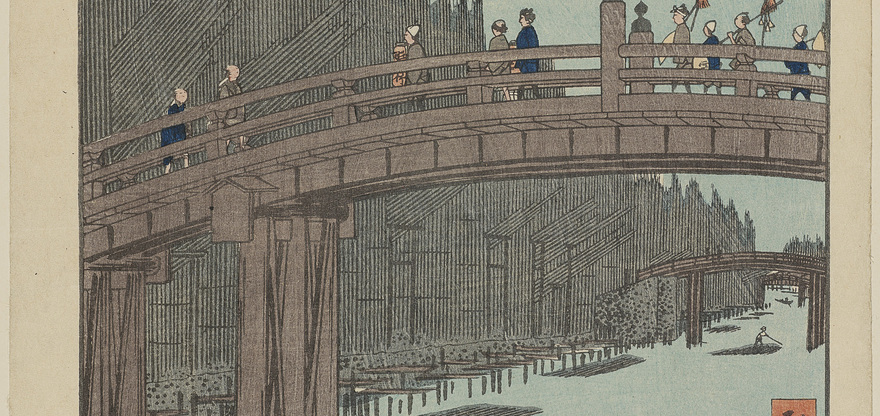

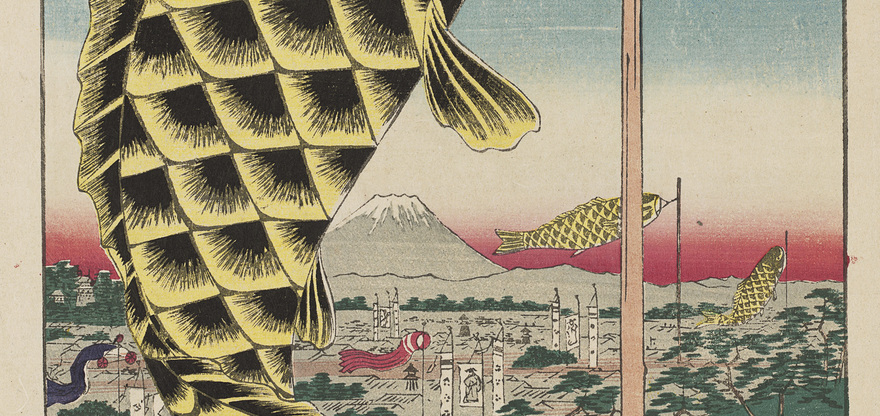

From the mid-nineteenth century to the early part of the twentieth century – beginning with the opening up of Japan to Western trade in 1858 – Western infatuation with all things Japanese brought about a radical renewal of the arts. In 1872, a French art critic and collector, Philippe Burty, even coined the term “Japonisme” to describe this fascination of the day. Some of the greatest American and European artists of the time were inspired by Japanese art and culture to create work of singular beauty. The collective Western imagination was particularly spurred on by Japanese prints known as ukiyo-e, graphic works which shine light on the ephemeral nature of life. The themes found in these images include annual flower blossoming celebrations, alluring geishas dancing in elegant kimonos, Kabuki theatre actors performing and the majestic Mount Fuji. Employing unusual viewpoints and asymmetrical compositions combined with decorative motifs and delicate colouring, ukiyo-e were a revelation for Western artists trained to depict the world around them from a single perspective.

Masterpieces with a Japanese Influence

Following an introduction highlighting Japan’s appeal for the West, the exhibition is built around four themes: Women, Urban Life, Nature and the Decorative Arts and Landscapes. It shows the various paths taken by American and European artists discovering Japanese art and culture, as seen in four major works by Claude Monet (1840–1926), including the wonderful Water Lily Pond, Green Harmony, 1900. Monet made this the topic of a series of paintings, like Zen meditations on nature and humanity of which nothing like it had been seen in the history of Western art. Another remarkable work is a scene of Breton peasants which attests to Paul Gauguin’s (1848–1903) interest in Japanese prints: Landscape with Two Breton Women, 1889. In the wonderful work by Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), Postman Joseph Roulin, 1888, the bright colours and stylized forms of Japanese prints are immediately recognizable; van Gogh collected and copied ukiyo-e prints and even organized an exhibition on the topic. Summer Night’s Dream (The Voice), 1893, by Edvard Munch (1863–1944), a Norwegian artist whose work is being shown in Québec for the very first time, lets us observe the motif of long aligned shafts, which his painting certainly picked up from Japanese works exhibited in Paris, or borrowed from avant-garde artists who had already incorporated these lessons into their work.

The Musée is also proud to be presenting rare prints by the Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), in particular Senju in Mushashi Province from the famous series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (around 1830–31, Edo period), a skilful composition in the very first large series of landscapes.

Among the work of the many decorative artists who appropriated Japanese forms and flora and fauna motifs such as chrysanthemums and butterflies, including Louis Comfort Tiffany and the potters of Newcomb College in the United States, Still Life with Azaleas and Apple Blossoms by the American artist Charles Caryl Coleman (1840–1928) and inspired by his vast and eclectic collection of decorative art, is an eloquent example. This work, made for a private home, was in harmony with the frame and with the motifs of the art objects around it. The aesthetic movement of the 1870s and 80s embraced the philosophy of art for art’s sake and promoted the integration of the fine arts and the decorative arts in skilfully designed interiors which were believed to be typical of Japanese homes.

Japan: An Irresistible Attraction

Following the opening of trade with Japan, many Westerners discovered the island nation through its art and artifacts. By the 1870s, plenty of opportunities for introduction to Japan existed in Europe and the United States, at specialty shops, World’s Fairs, and exhibitions, including an impressive and highly influential display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Artists and collectors were among the first to appreciate the exotic wares arriving in large quantities on Western shores, but the general public soon caught on to the wonders offered by woodblock prints, bronzes, lacquerware, and other unfamiliar objects produced by a culture that had once seemed impossibly remote. These goods soon appeared in Western works of art, reproduced literally as documents of taste and collecting habits, or creatively reimagined as elements of a new style. Views of Japan also became part of the repertoire of artists who were among the early travelers to visit the country on long voyages of discovery and learning. Their works in turn spread images of Japan to an appreciative audience. The paintings, prints, and decorative arts on display in this gallery demonstrate the type of Japanese art available to Western audiences in the late nineteenth century, as well as a rich sampling of the initial ways that artists engaged with Japan as collectors, travelers, and enthusiasts.

Women

As women assumed more active roles in public life at the turn of the century, they became important participants in a number of fin-de-siècle artistic movements, especially japonisme. They were by turns collectors in the market for exotic goods, artists inspired by the art and culture of the foreign land, and themselves subjects of numerous works of art. The taste for Japan was associated early on with female consumers who wore imported silks and decorated their homes with curiosities. Paintings of European beauties in such gowns were among the first Japan-inspired works of art in the West, starting in the 1860s and 1870s. Many Westerners imagined the country to be replete with geishas and courtesans, symbolized by Madames Chrysanthème and Butterfly, the tragic and fictitious heroines of popular novels, plays, and operas. The frequency with which attractive women, or male actors dressed as female beauties, appear in Ukiyo-e art reinforced this stereotype for some Western observers. Others were challenged by the Japanese artists’ frank portrayal of the most intimate or everyday activities of their subjects as well as the glamorous aspects of their existence. Elements borrowed from the Japanese seemed well-suited to a variety of ways of depicting woman, ranging from traditional portraiture to avant-garde experiments with unusual subjects and styles.

City Life

Great changes in cities across Europe and the United States set the stage for the cult status Japanese goods achieved in the late nineteenth century. A distinct urban culture emerged during this period, a result of architectural transformation, the Industrial Revolution, and the merging of public and private spheres. The excitement of this electrifying time captivated a generation of artists who were compelled to move away from tradition toward new subjects and styles that matched the character of modern life. They were fascinated by the major category of ukiyo-e prints devoted to depictions of city life and its diversions. Many welcomed the discovery that the Japanese had engaged seriously with subject matter that critics had dismissed as frivolous or superficial. “These Japanese artists confirm my belief in our vision,” wrote the Impressionist Camille Pissarro, after seeing an exhibition of ukiyo-e in 1893. The newness of Japanese art seemed well matched to the novelty of popular activities like horse-racing and cabarets, as well as to the sensations of immediacy, speed, and theatricality they produced. It also offered a range of formal possibilities to artists experimenting with abstraction and symbolism. City life not only encouraged interest in Japanese art, it fostered the development of artistic movements that incorporated Japanese elements so thoroughly that they became part and parcel of Modernism.

Nature and Decorative Arts

Natural motifs and styles inspired by Japanese art are hallmarks of several major Western artistic movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This is especially true for the decorative arts as well as printmaking, poster design, and photography, all of which previously had been considered minor or commercial in comparison with painting and sculpture, but which drew increasingly serious attention in the fin de siècle. Critics imagined Japanese artists and designers to be universally dedicated to the appreciation of flora and fauna and urged their contemporaries to similarly devote their efforts. “The art of Japan leads us to return to nature” was a sentiment shared by numerous writers. A wide variety of organic forms appeared in the Japanese prints, lacquers, silks, bronzes and ceramics that saturated the Western market in the late nineteenth century. These were especially welcomed by the artists and collectors who valued the revitalization of the domestic interior and incorporated natural references into skillfully designed rooms. Their commitment to the highest level of creativity in all media, whether fine or decorative, found parallels in Japanese culture. Siegfried Bing, one the great promoters of Japanese art, commented that “Nature” is the Japanese artist’s “sole, his revered teacher, and her precepts form the inexhaustible source of his inspiration.”

Landscape

Japanese approaches to color, perspective, and light in the depiction of landscapes offered compelling possibilities to Western artists already enamored of the country’s sensitivity to nature and its ever-changing beauty. Many painters discovered Japanese art around the same time that they became aware of the new science of color, especially the theories of nineteenth-century chemist Michel-Eugène Chevreul, and increasingly questioned the Western landscape tradition. Some observers remarked that the bright colors of ukiyo-e prints made them feel as though veils had been lifted from their eyes. Instead of using shadows to create convincing three-dimensional forms, the Japanese employed contrasts in color, the repetition of shapes, and a focus on essential features to animate views of such iconic sites as Mount Fuji. A number of these pictorial devices became part of the Western repertoire. Western artists were drawn, for example, to the atmospheric effects featured in ukiyo-e prints, concentrating on the ephemeral nature of the seasons and times of day. Other Japanese motifs that became essential elements of the new Western styles were the repeated trees, trellises, and gridlike structures that offered a way of organizing landscape, which was legible while also decorative or symbolic. The overhead perspective known as a “birds’ eye” view also came into favor, and was especially useful in translating a personal reaction to a place, be it as majestic as the Grand Canyon or as quietly sublime as a water lily pond in Giverny.

Give us your feedback